Sitting in a Chair for Too Long Is Bad Even if You Exercise — Here’s Why

Think you're immune from the adverse health effects of prolonged sitting in a chair because you're physically active? Well, think again.

Sitting is the new smoking.

Chances are, you’ve seen that headline/caption or a more morbid variation. E.g., “Sitting too much will kill you 🪦”.

If you follow a structured exercise regimen, like 2x strength training + 3x cardio sessions weekly, you may go, “Psssh, *rolls eyes* irrelevant, because I’m so fit — skip,” and move on to whatever’s next on your feed.

🚨 Well, newsflash: physical activity does not make you invulnerable to the harmful health effects of prolonged sitting in a chair.

You’ll find out why in this article.

(Before we proceed, you might want to pick your jaw up from the floor first.)

Why is prolonged sitting in a chair bad for you?

OK. Let’s start from the beginning.

Why is prolonged sitting in a chair bad for you? It all comes down to its sedentary nature.

When you sit in a chair, you’re not demanding much of your muscles. As a result, they don’t need as much glucose and/or oxygen to generate the energy they need to keep running (in comparison to when you’re moving or exercising).

The downstream effects of that include:

- Decreased blood flow (impacting the cardiovascular system)

- Lowered insulin sensitivity (worsening glycemic control)

It doesn’t end there.

Sitting in a chair also bends major arteries in the lower limbs, particularly under the thighs, leading to a blood flow pattern known as turbulent flow, blood pooling, impaired circulation, and endothelial dysfunction.

This may drive up blood pressure.

Oof, anything else? Unfortunately, yes. Long periods of uninterrupted sitting also negatively affect body composition — increasing body fat mass while decreasing lean body mass … you probably already know how the rest of that story goes (carrying excess fat is linked to heart disease, fatty liver diseases, etc.).

“But,” you may be wondering, “Why doesn’t exercise offset any of that?”

Why doesn’t exercise offset the effects of prolonged sitting in a chair?

Here’s the thing. It does, a little bit, but it’s not enough.

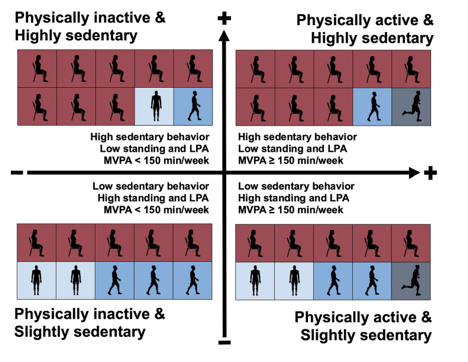

To understand why, look at the 4 quadrants below.

The more sedentary behavior (“red blocks”) you accumulate throughout the day, the more precarious it is for your metabolic health. We’re not just making this up, BTW. A large body of evidence finds that prolonged sitting is bad for you, even if you exercise:

- 2024 study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association (mortality risk)

- 2019 systematic review published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine (risk of developing chronic conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and stroke)

- 2017 study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine (premature mortality risk)

… we could go on but won’t because we trust we’ve gotten the point across.

Tips that’ll help you avoid prolonged sitting in a chair

Sit less, move more.

*blows raspberry* Was that helpful? Not at all, right? That was like telling you to “just eat healthier” without telling you how (e.g., how many fruits and vegetables daily? Or should you use meal replacement shakes?)

A more specific recommendation you could work with instead is avoiding sitting in a chair for longer than 30 to 60 minutes in a single stretch.

Set an alarm if you have to. And whenever it buzzes or rings, get off your chair and:

- Do some bodyweight exercises (squats, lunges, push-ups)

- Walk over to your favorite colleague for a quick catch-up

- Stretch

- … anything you want, really, as long as you move

Now, if you’re thinking of getting a standing desk, our honest opinion is that it isn’t worth it.

Standing isn’t that much more active than sitting — because, ultimately, what you’re doing is still the same: staying relatively still, which doesn’t tax your muscles.

Besides, extended periods of standing could be harmful to musculoskeletal health, causing symptoms such as:

- Muscle fatigue

- Leg swelling

- Varicose veins

- Pain and discomfort in the lower back and extremities (hips, knees, ankles, and feet)

For those who’re still interested in “upgrading” their workstation, a better investment for your metabolic health might be an under-desk treadmill.

That said, it’s unlikely that you’d be able or even wish to sustain using it for the entirety of your work duration, so please consider the following before swiping your credit card on a > $200 under-desk treadmill:

If the under-desk treadmill idea isn’t as appealing as it was 5 minutes ago, don’t worry.

You really don’t need a dedicated machine to get your movement in. Research shows that interrupting prolonged sitting time with as little as 2-5 minutes of light walking every 20-30 minutes of sitting in a chair is sufficient to improve blood glucose, fat, and cholesterol levels.

Don’t neglect structured exercise

Limiting the amount of time that you spend sitting in a chair is important. But it’s also important that you continue sticking to an exercise regimen that helps you meet the following physical activity requirements:

- At least 150-300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity

- 2x or more muscle-strengthening activities that involve all major muscle groups

… weekly.

A beginner to the gym? Or just looking to spice up your strength training routine?

No matter which you are, GymStreak’s got you covered with its personalized training plans, customized to your lifting experience, fitness goal, time availability, and more. It also comes with an in-built nutrition tracker, so you can easily see if you’re fueling your body right.

Check it out:

Workout Programming + Nutrition Tracking, Off Your Hands

*sigh of relief* We'll guide you through it all — step-by-step. Just download the app, and you'll be making progress toward your dream body like never before.

References

Bailey, Daniel P., et al. “Sitting Time and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine, vol. 57, no. 3, Sept. 2019, pp. 408–16. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.04.015.

Dempsey, Paddy C., et al. “Benefits for Type 2 Diabetes of Interrupting Prolonged Sitting With Brief Bouts of Light Walking or Simple Resistance Activities.” Diabetes Care, vol. 39, no. 6, Apr. 2016, pp. 964–72. Silverchair, https://doi.org/10.2337/dc15-2336.

Dunstan, David W., et al. “Breaking Up Prolonged Sitting Reduces Postprandial Glucose and Insulin Responses.” Diabetes Care, vol. 35, no. 5, Apr. 2012, pp. 976–83. Silverchair, https://doi.org/10.2337/dc11-1931.

Duran, Andrea T., et al. “Breaking Up Prolonged Sitting to Improve Cardiometabolic Risk: Dose–Response Analysis of a Randomized Crossover Trial.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, vol. 55, no. 5, May 2023, p. 847. journals.lww.com, https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000003109.

“Health Risks of Overweight & Obesity - NIDDK.” National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/adult-overweight-obesity/health-risks. Accessed 16 May 2024.

Koohsari, Mohammad Javad, et al. “Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep Quality.” Scientific Reports, vol. 13, no. 1, Jan. 2023, p. 1180. www.nature.com, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-27882-z.

M. Diaz, Keith, et al. “Patterns of Sedentary Behavior and Mortality in U.S. Middle-Aged and Older Adults.” Annals of Internal Medicine, Sept. 2017. world, www.acpjournals.org, https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M17-0212.

Nguyen, Steve, et al. “Prospective Associations of Accelerometer‐Measured Machine‐Learned Sedentary Behavior With Death Among Older Women: The OPACH Study.” Journal of the American Heart Association, Mar. 2024. world, www.ahajournals.org, https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.123.031156.

Physical Activity. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity. Accessed 16 May 2024.

Pinto, Ana J., et al. “Physiology of Sedentary Behavior.” Physiological Reviews, vol. 103, no. 4, Oct. 2023, pp. 2561–622. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00022.2022.

Waters, Thomas R., and Robert B. Dick. “Evidence of Health Risks Associated with Prolonged Standing at Work and Intervention Effectiveness.” Rehabilitation Nursing Journal, vol. 40, no. 3, June 2015, p. 148. journals.lww.com, https://doi.org/10.1002/rnj.166.