Why Training Injured Can Speed up Recovery and Performance

Do you think you can improve strength in your injured limb by training your other? From what we know so far, it is entirely possible to train one limb and increase strength or mitigate strength losses in the other limb; this concept is also known as the "cross-education phenomenon."

Let's assume for a second that your left bicep is injured?

Do you think you can improve its strength by training your right arm instead? Let's not keep you waiting until the end of this article. From what we know so far, it is entirely possible to train one limb and increase strength or mitigate strength losses in the other limb; this concept is also known as the "cross-education phenomenon."

You may be wondering, “Okay then – you’ve just given me the answer, why do I need to continue reading this article?” Excellent point.

See: while the phenomenon is well-known, the fitness industry hasn't known how different training configurations – drop sets, regular sets, or cluster sets – affect the magnitude of the cross-education effect. Until now, that is.

In May 2019, a group of researchers set out to examine if traditional sets or cluster sets were better at eliciting the cross-education effect, and the results might surprise you. So, keep reading if you want to find out how you should train to mitigate strength losses when suffering from a unilateral injury.

Wait – what are cluster sets?

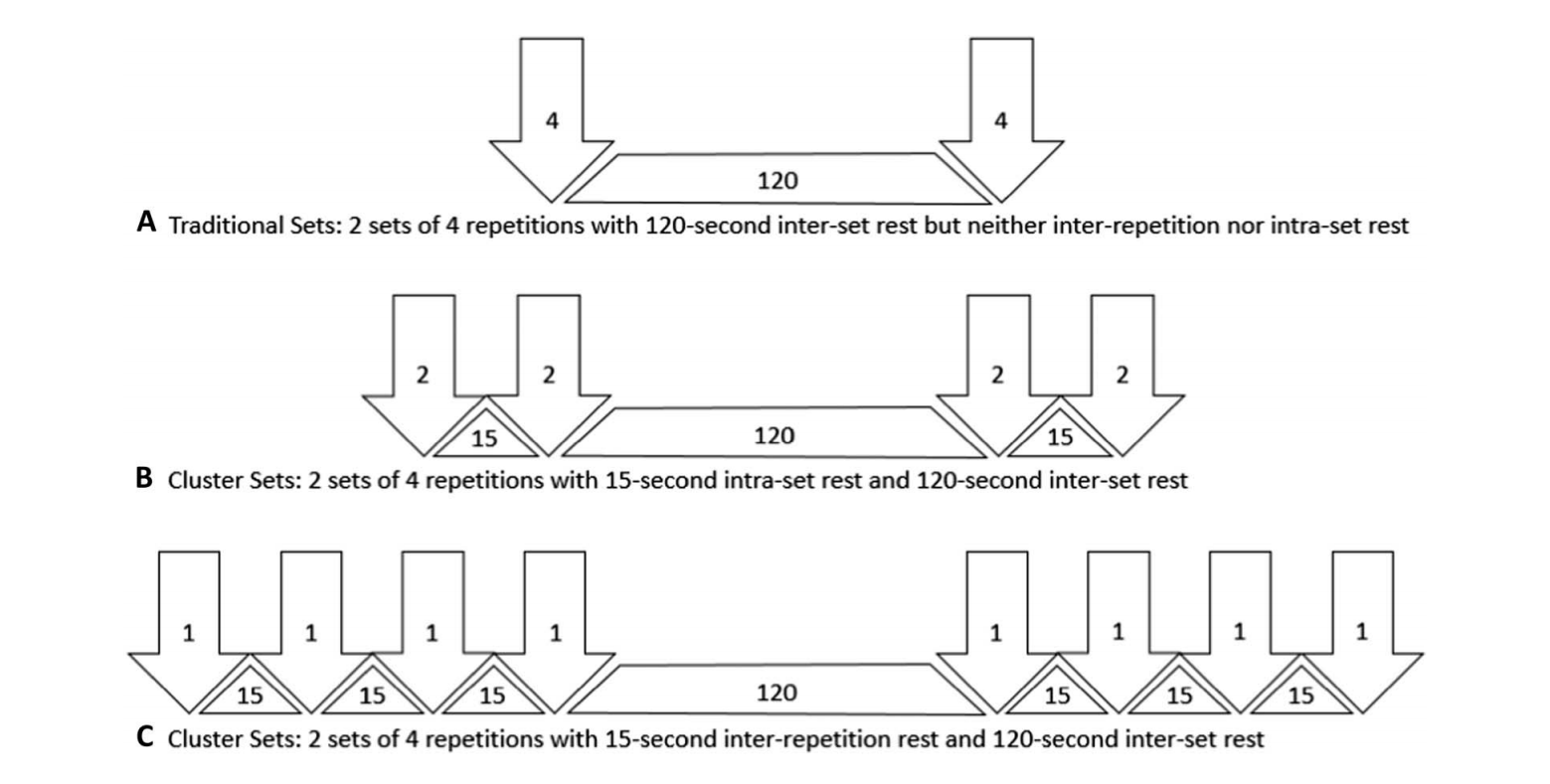

Cluster sets are sets that feature built-in, intra-set rest periods; they are usually performed to allow the lifter – you, in this case – to push through more weight and reps, increasing the total weight lifted in a single session. Still too abstract? Don't worry – we've got you covered.

An example of a cluster set would look something like this when your set consists of 8 repetitions:

1. Perform two reps

2. Rest for 30 seconds

3. Repeat #1 and #2 until you've completed eight reps

Also, for the convenience of anyone new to lifting, traditional sets are simply what nearly everyone else does in the gym: a set of 10 reps will be completed rep by rep with no rest in between until all ten have been completed.

The research

The investigators hypothesized that participants who utilized traditional sets in their training sessions would increase the strength of the injured limb to a greater extent than the cluster set group, and here's what their study involved:

Subjects – The researchers recruited 35 men and women between 21 and 38 years old; all participants were physically active, but no further information was given regarding training experience.

Protocol – Participants were split into three groups:

Traditional training: only the dominant limb was trained

Cluster training: only the dominant limb was trained

Control group: participants did not train at all

Findings – In short, the traditional set group came out on top. Traditional set training produced a 7.3% strength increase in the non-trained limb, while the other groups experienced no statistically significant change in strength. The researchers did not observe hypertrophy effects in the non-trained limb across all three groups.

How do the results apply to real-world training?

Excellent – training one limb can increase strength in the other; this study’s findings are congruent with another recent meta-analysis done in 2017, which found an average increase of 9.4% in the non-trained limb.

Based on both papers' recommendations, if you want to achieve the cross-education effect, you need to train for at least 4 – 12 weeks with at least 60% of 1RM (One Rep Max). And as of now, traditional sets seem to be the best method of eliciting the cross-education phenomenon.

Cross education is pretty cool – come on, increasing strength when seemingly not training? – but how can it benefit you?

During times of injury

This is probably cross education's most apparent benefit. After all, we did start the article with this point in mind. So, if you have an injury to one limb and you can't train it for a while, training the non-injured limb will help maintain strength in the injured one.

Strength imbalances between limbs

The cross-education effect might be able to help you even out any strength imbalances between the limb, especially if the weaker limb is the non-dominant limb. Therefore, if you have a strength imbalance and you perform most of your training with a barbell or with bilateral exercises, then it may be worth including some unilateral dumbbell movement.

However, it's critical to note that hypertrophy does not occur alongside strength increases with the cross-education phenomenon. You cannot merely train your right leg and expect to put on muscle mass on your left; it doesn't work like that. If you want faster muscle growth, be sure to check out our articles on training to failure and the power of the mind-muscle connection.

Bottom line

Ultimately, the cross-education phenomenon is probably most useful during times of injury; you can make use of this effect to mitigate strength losses in the injured limb by training the other. Also, since traditional sets are much better at eliciting strength increases in the injured limb, you can maximize this observed effect by stretching out your rest periods. But – why? Find out by reading this article.

It can be pretty challenging to find a workout partner who’s willing to train around your injuries alongside you. If you don’t want to train alone, download GymStreak! Our app's smart workouts ensure that you stay on top of your individualized training plan even when injured. So – what are you waiting for? Download it now!

References

Fariñas, J., Mayo, X., Giraldez-García, M. A., Carballeira, E., Fernandez-Del-Olmo, M., Rial-Vazquez, J., … Iglesias-Soler, E. (2019). Set Configuration in Strength Training Programs Modulates the Cross Education Phenomenon. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003189

Manca, A., Dragone, D., Dvir, Z., & Deriu, F. (2017). Cross-education of muscular strength following unilateral resistance training: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 117(11), 2335–2354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-017-3720-z