Which Recovery Techniques Should You Use for Sore Muscles?

Struggling with sore muscles? Here are 4 of the best, science-backed recovery techniques that'll help you get back to the grind ASAP.

The key to alleviating delayed onset muscle soreness (i.e., DOMS) is time ⌚

You know that. But when you’re struggling to get up from the bed, climb the stairs needed to get to your favorite coffee joint, or maybe even to put on your clothes … you can’t help but wonder, “Is there a way to speed up the recovery process?”

Well, there is.

As a matter of fact, there are several research-backed recovery techniques that’ll truly speed up your healing process so that you can get right back to the grind.

Continue reading to find out what they are, plus how you can incorporate them into your life for quicker relief from sore muscles.

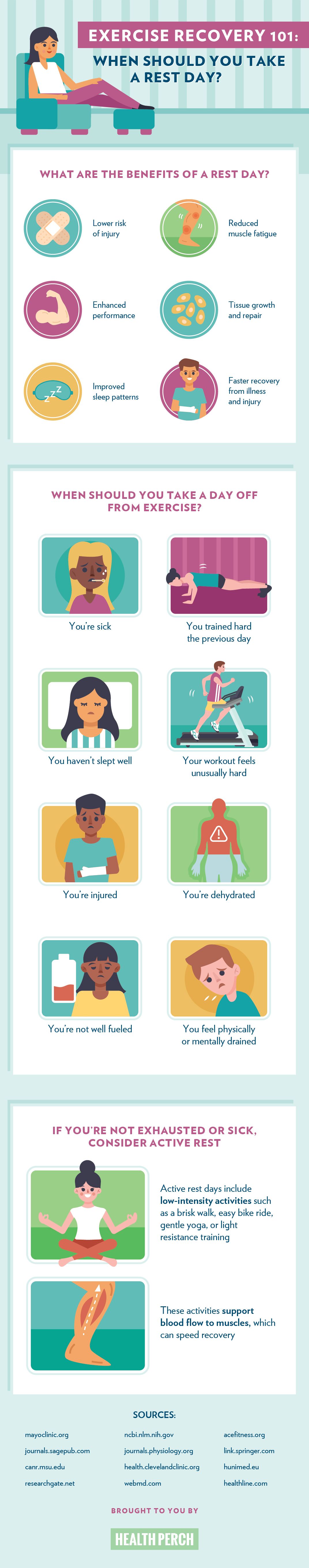

1: Active recovery

Wait. Active recovery?

Hear me out: while more movement may be the last thing on your mind when you’re already, well, so sore, keeping your body active helps promote blood flow – which “speeds up” not only the delivery of nutrients (e.g., amino acids, the building block of protein) to healing muscles but also the removal of waste products.

For instance, this 2010 study published in the International Journal of Sports Medicine found that triathletes who’d followed a HIIT session with active recovery (via swimming) showed superior exercise performance the next day compared to those who didn’t.

Uh-oh. What if you can’t swim? Well, who said that was the only movement modality you could do?

In truth, the aim of active recovery is to get the blood moving; that means you can do whatever activity your heart desires.

Tai chi, yoga, steady-state walking or cycling, hiking. There are so many options.

That said, be mindful that active recovery days are meant for recovery. Meaning? You shouldn’t be pushing yourself to the limit (FYI: tackling the Welsh 3000s doesn’t count as active recovery!)

Instead, keep your exertion to a maximum of 60% of what you'd typically experience during your regular workout days.

2: Massage

Chances are, you probably already know the benefits a solid rubdown could bring. Amped immunity, anxiety relief, and even improved sleep quality. Well, here’s something else you could add to the list: sweet relief from sore muscles.

The research on this recovery technique is solid. How solid, you ask?

Just reference this impressive 2018 meta-analysis published in Frontiers in Physiology.

Synthesizing data from 99 separate studies, the researchers compared 10 well-known recovery techniques – including active recovery, stretching, compression garments, and cryotherapy.

The results? The meta-analysis concluded that massage had the most considerable effect on muscle soreness.

That said, it’s worth noting that the massage sessions took place immediately post-training. Meaning? It isn’t clear whether a massage the day after a heavy legs day would make your legs any less … for lack of a better word: jelly.

Obviously, this highlights several disadvantages of relying on massage as a recovery technique for sore muscles after a workout.

First and foremost, time. Who has 4 hours to spare in a day (2 hours for a workout, then 2 hours for a massage session – including transportation time)?

And perhaps, more importantly, there’s the financial aspect of it. Assuming a single massage session costs £50, someone who trains thrice a week can expect to fork out an additional £600 in the name of less sore muscles!

These considerations rule out massage as a viable recovery technique for most of us, especially when hitting the daily protein requirement is already so expensive!

3: Compression clothing

So, what is someone who’s both time - and money-poor to do if they still wish to seek quicker relief from those achy, sore muscles? Two words: compression garments.

At least, that’s what the same 2018 meta-analysis (as mentioned earlier) concludes as the second-best recovery technique for DOMS.

But how? Once again, as with active recovery and massage, compression garments help speed up the healing process by improving blood flow.

Before you run out and snatch the first compression garment you lay your eyes on, though, understand that they only work if they’re of the right size for you. In other words: they need to fit snugly (because the pressure is crucial for enhancing blood flow).

Oh, and this probably doesn’t need to be said, but here goes anyway. You should wear the compression garment around the region you wish to stimulate recovery in.

While compression socks are great for keeping your feet warm, they aren’t going to do much in alleviating muscle soreness in your quads after a heavy squatting day, for example. (But you know that already … right?)

4: Cold water immersion

Plunging into cold water to assuage the feeling of sore muscles after an intense workout session: this is something we’ve all seen competitive athletes – in events like the Olympics, various strong man competitions, and even CrossFit – do.

But just because they do so doesn't necessarily mean that you should do it.

Now, don’t get me wrong. It isn’t that cold water immersion doesn’t help boost post-workout recovery from sore muscles. It does.

Only, the mechanism through which it does so isn’t the best news for long-term muscle hypertrophy and growth.

To understand why you'll first need to get some background on how your muscles grow in the first place. See: when you lift weights, you create tiny (microscopic) tears in your muscle fibers. This, in turn, kickstarts an “inflammatory” pathway that’s key to the healing process – where your body sends various chemicals and molecules to the “damaged regions”.

When you repeatedly "damage" and heal your muscle fibers, they get bigger and stronger over time.

And now, back to cold water immersion.

What you need to understand is that cold water immersion essentially stops inflammation from taking place. So, while it does relieve muscle soreness, it also – unfortunately – hinders the hypertrophy process.

As a result, the only occasion where it’d make sense for you to make use of cold water immersion as a recovery technique is where you’re participating in a competition where there are 2 events in close succession (e.g., on the same day or 24 hours of each other).

It never hurts to relook your workout programming

Run through the recovery techniques in this article but still find that you're sore for more days than you’re exercising in a week?

Then it might be time to relook your workout programming. Perhaps there’s something you’re doing wrong there. If you’re not sure what your mistake is, exactly, well … stop grasping at straws in the dark.

Let GymStreak help you. You can count on this AI-enabled personal trainer app to develop the most effective training program that’ll help get you to your dream physique ASAP.

References

Davies, V., Thompson, K. G., & Cooper, S.-M. (2009). The effects of compression garments on recovery. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23(6), 1786–1794. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b42589

Dupuy, O., Douzi, W., Theurot, D., Bosquet, L., & Dugué, B. (2018). An Evidence-Based Approach for Choosing Post-exercise Recovery Techniques to Reduce Markers of Muscle Damage, Soreness, Fatigue, and Inflammation: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Physiology, 9, 403. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.00403

Lum, D., Landers, G., & Peeling, P. (2010). Effects of a recovery swim on subsequent running performance. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 31(1), 26–30. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1239498

Menzies, P., Menzies, C., McIntyre, L., Paterson, P., Wilson, J., & Kemi, O. J. (2010). Blood lactate clearance during active recovery after an intense running bout depends on the intensity of the active recovery. Journal of Sports Sciences, 28(9), 975–982. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2010.481721

Roberts, L. A., Raastad, T., Markworth, J. F., Figueiredo, V. C., Egner, I. M., Shield, A., Cameron-Smith, D., Coombes, J. S., & Peake, J. M. (2015). Post-exercise cold water immersion attenuates acute anabolic signalling and long-term adaptations in muscle to strength training. The Journal of Physiology, 593(18), 4285–4301. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP270570