Why Am I Having a Hard Time Losing Weight? (Stop Blaming Yourself)

If you've ever shaken your fists at the sky and asked, "Why am I having a hard time losing weight?!" — read this article. It isn't your fault.

The principle of weight loss is straightforward. It all comes down to balance.

Decrease your calorie consumption, increase your energy expenditure, or do both to achieve a deficit and BAM! Smaller numbers on the scale.

But try putting that into practice, and you'll often be sorely disappointed.

On the bright side (?), you’re not the only one struggling. Research suggests that anywhere between 30% to a jaw-dropping 95% of dieters fail to lose weight and/or regain more weight than they lost within 4 or 5 years. Depressing.

So … why? Why is the human body so set against weight loss?

And, more importantly, why isn’t everyone’s body equally, stubbornly resistant to losing the *chonks*? (Because we all know That Someone who lost and kept 20 kg off — without even breaking a sweat or experiencing 1,785 breakdowns daily.)

Find out here; this article is dedicated to anyone who’s ever shaken their fists at the sky, screaming, “Why am I having a hard time losing weight?! 🤬”

It isn’t your fault. Well, most of the time, at least.

#1: Your threshold for low energy availability

The first part to answering your question (i.e., "Why am I having such a hard time losing weight?!") has to do with something called energy availability (EA).

EA is defined as the amount of dietary energy available to sustain all physiological functions — think respiration, digestion, and excretion — after subtracting the energetic cost of exercise. It’s expressed relative to an individual’s lean body mass.

(Total Calorie Intake – Exercise Expenditure) / Lean Body Mass

Now, think about what happens to EA when your calorie intake goes down while your exercise expenditure goes up (remember, this is what you need for weight loss); assume lean body mass stays constant for simplicity’s sake.

That’s right. EA decreases in response.

Meaning? Your body has lesser “leftover” energy available for physiological function.

If you continue ramping up your calorie deficit, you’ll eventually reach the point of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sports (RED-S), a phenomenon where your body has insufficient energy to sustain:

- Peak sports performance, and

- Optimal health

Which is where you’d run into worrying symptoms, such as suppression of resting metabolism rate*, weakened bones, menstrual irregularities, poor mood, immune dysfunction, increased fatigue, and sleep disturbances.

But how low is too low?

Or, in other words, what’s the exact EA value that you should start worrying about RED-S?

30 kcal/kg/LBM/day is a good guideline.

But there can be substantial individual variation.

Some lucky people may be fine and dandy with 20 kcal/kg/LBM/day, while others may feel zombified even though they're running on 45 kcal/kg/LBM/day.

This is why some people still have that spark in their eyes while dieting (lucky b*tches!)

Wait. So how does low energy availability answer your question, “Why am I having a hard time losing weight?!”

OK. Imagine you're constantly down with the sniffles, irritable, and tired (you haven't been sleeping well). How likely are you to stick to your workout routine? And how likely are you to turn to your comfort foods for, um, comfort? Yeah.

#2: Adaptive thermogenesis

So, remember what we said about RED-S leading to a suppression of your resting metabolism rate?

That pretty much describes adaptive thermogenesis, or AT for short, which we’ve written in-depth in the following articles (we encourage you to check them out!)

For now, though, here is a brief lil' intro to AT.

It refers to a greater-than-predicted drop in an individual's metabolic rate after weight loss — beyond what should be expected based on body composition (i.e., lean and fat mass).

Why? Because of low energy availability.

See: with RED-S, your body's already struggling to get enough energy even to help "keep the lights on". So, imagine where your body would place non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) on its priority list.

Uh-huh. At the very bottom (if at all).

That means you won't be moving about or fidgeting as much, lowering your energy metabolism.

Just so you know: the drop in NEAT levels can account for as much as 85% to 90% of the decline in energy expenditure commonly attributed to AT!

Alright. So, low EA and, in turn, AT have helped unravel the mystery of why weight loss and weight loss maintenance are so tricky. Kind of. Because there's actually 1 more crucial part to the answer to your question, "Why am I having a hard time losing weight?!" ✊

#3: Body fat “set point”

Here’s the thing. Your body might be trying to maintain its body fat set point.

What's that, you ask? Well, it goes back to set point theory, the idea that your body has a unique, innate “preset weight” that it tries to maintain.

Think of it this way: your body’s like a petulant child who refuses to go to summer camp because they don’t want to leave their comfort zone.

In this case, your “set weight” is your body’s comfort zone.

Without going into too much detail and boring you, the set point theory states that your body regulates energy intake and expenditure to get you as close to your body fat set point as possible.

E.g., if you're below the set threshold, you'd get hungrier (you eat more; way more) and lazier (you move less; way less), so you put on weight.

Sounds reasonable enough.

But, in actuality, it's too simplistic a theory.

If it were wholly accurate, it'd mean that people would find it difficult to lose weight and put on weight, which doesn't make sense.

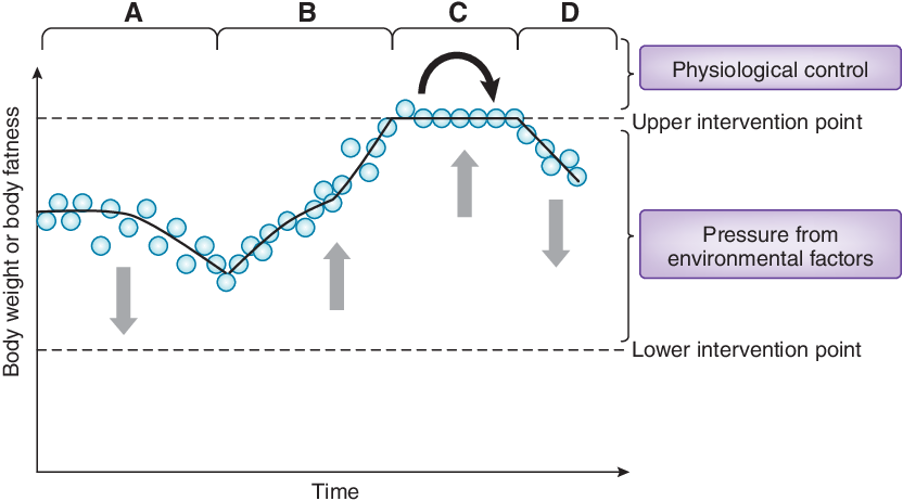

So, in its place, scientists proposed a different theory: the “dual-intervention model” of body weight regulation.

It argues that your body prefers to keep your weight within a range.

As shown in the image above, there are upper and lower points where physiological factors (e.g., appetite hormones) influence energy intake and expenditure. But between those points are where environmental factors (i.e., what you do) dominate.

So, unfortunately, if you're someone who's been screaming, "Why am I having a hard time losing weight?" you might have a more elevated "low intervention point" than the average person.

The game may be rigged, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t play

Wow, everything’s working against me.

RED-S. Adaptive thermogenesis. And your body’s lower intervention point. It might seem like your body’s conspiring against you — preventing you from achieving your physique goals.

But does this mean you should throw in the towel and give up? Just let your body weight hang around the upper intervention point?

Please, no.

As clearly shown in the graph, there is generally a great distance between your lower and upper intervention points.

You can do plenty of things to stay closer to your lower intervention point (where you'd typically enjoy a cleaner bill of health and look closer to your ideal physique) than the upper intervention point.

Things like … Ozempic? Uh, not really; see why below:

But more like:

🍇 Building your diet around minimally processed foods, fruits, and vegetables

🏃 Increasing physical activity

🔌 Actively combating weight loss fatigue

🏋️ And, of course, lifting lots of weights

Need help getting started with the last bit? Gymstreak is perfect for you. This smart, AI-powered personal trainer app tailors all your workout sessions to your fitness goals and needs.

Here’s a little sneak peek:

Workout Programming + Nutrition Tracking, Off Your Hands

*sigh of relief* We'll guide you through it all — step-by-step. Just download the app, and you'll be making progress toward your dream body like never before.

References

Areta, José L., et al. “Low Energy Availability: History, Definition and Evidence of Its Endocrine, Metabolic and Physiological Effects in Prospective Studies in Females and Males.” European Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 121, no. 1, Jan. 2021, pp. 1–21. Springer Link, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-020-04516-0.

“Dieting Does Not Work, UCLA Researchers Report.” UCLA, https://newsroom.ucla.edu/releases/Dieting-Does-Not-Work-UCLA-Researchers-7832. Accessed 16 Aug. 2023.

Medicine, Daniel Engber, Nature. “Unexpected Clues Emerge About Why Diets Fail.” Scientific American, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/unexpected-clues-emerge-about-why-diets-fail/. Accessed 16 Aug. 2023.

Rosenbaum, M., and R. L. Leibel. “Adaptive Thermogenesis in Humans.” International Journal of Obesity (2005), vol. 34 Suppl 1, no. 0 1, Oct. 2010, pp. S47-55. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2010.184.

Speakman, John R., David A. Levitsky, David B. Allison, Molly S. Bray, John M. de Castro, et al. “Set Points, Settling Points and Some Alternative Models: Theoretical Options to Understand How Genes and Environments Combine to Regulate Body Adiposity.” Disease Models & Mechanisms, vol. 4, no. 6, Nov. 2011, pp. 733–45. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1242/dmm.008698.

Speakman, John R., David A. Levitsky, David B. Allison, Molly S. Bray, John M. De Castro, et al. “Set Points, Settling Points and Some Alternative Models: Theoretical Options to Understand How Genes and Environments Combine to Regulate Body Adiposity.” Disease Models & Mechanisms, vol. 4, no. 6, Nov. 2011, pp. 733–45. Semantic Scholar, https://doi.org/10.1242/dmm.008698.

Statuta, Siobhan M., et al. “Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S).” British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 51, no. 21, Nov. 2017, pp. 1570–71. bjsm.bmj.com, https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-097700.